On a quiet recent evening, I came across a BBC headline: “Earth’s inner core may have changed shape, say scientists”. My mind stopped in its tracks.

If asked yesterday morning about the Earth’s core, I would have mumbled something about magma and the crust. To my memory, I have never given this foundational question any thought whatsoever. All my life, I have carried around a half-formed, uncontemplated notion about what lies beneath my very feet.

How had I never wondered about this most fundamental aspect of our planet? What a profound gap in curiosity and understanding. The past 24 hours, I have been making up for lost time. I am stunned by what I’ve learnt.

To give some context, I’ll try and share a taste of what I have found so revelatory.

…

The distance from ourselves to the Earth’s centre is 6,371km – a distance equal to 800 Mount Everests stacked on top of each other. When our planet formed, 4.5 billion years ago, the earth was entirely liquid. Over time, the heaviest elements sank to form the core, while the lightest floated up to become the crust we live on.

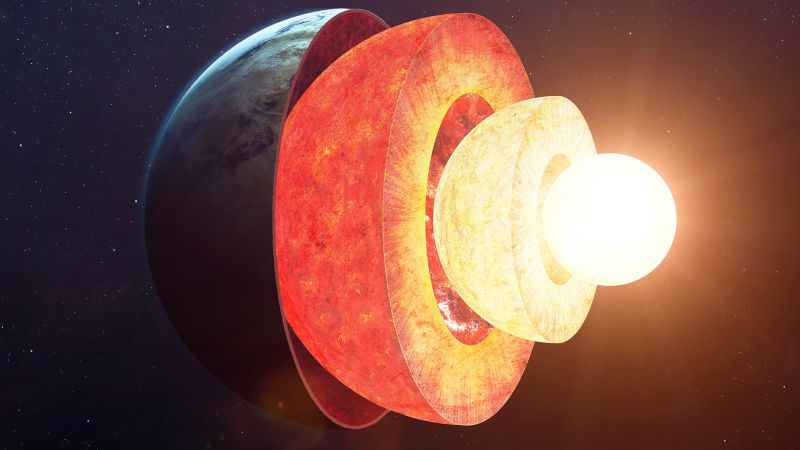

As far as we know, the Earth has four main layers. The first is the crust, the layer on which we live. Maxing out at 80km thick, it makes up less than 1% of the planet’s radius and volume. Underneath the crust sits the mantle – not liquid magma as commonly thought, but solid rock that can flow very slowly, moving just a few centimetres per year and representing 65% the of Earth’s mass.

Inside the mantle sits the core, composed of an outer and inner core. The outer core is a vast ocean of super-hot liquid metal, and is about the same size of Mars. The churning of these molten metals generates electrical currents, which in turn generate our electromagnetic field. The direction of the field flips every few thousand years, changing the location of North and South.

The inner core is a solid ball, composed of 80% iron and 20% nickel, spinning slightly faster than the Earth itself (making a complete rotation of the Earth every 400 years). The size of the moon and almost the same temperature as the surface of the sun (6,000°C), its volume is 5x that of all the world’s combined oceans. Iron melts at 1,538°C; nickel melts at 1,455°C. The core’s solidity is derived from the enormous pressure (3.6 million times the surface’s pressure), at which the atoms cannot physically move.

How do we know all this when we’ve barely scratched the surface? The deepest hole ever dug – the Soviet Union’s Kola Superdeep Borehole – reached just 7.6 miles down. Our knowledge comes instead from brilliant scientific detective work: seismic waves from earthquakes, magnetic field measurements, physics, and computer modelling.

The story of this understanding is itself remarkable. In 1863, Lord Kelvin tried to calculate Earth’s age based on cooling rates. In 1906, Richard Dixon Oldham discovered the liquid outer core by studying earthquake waves. In 1936, Inge Lehmann found the solid inner core by spotting unexpected patterns in seismic data. Each discovery built on the last, as generations of scientists – physicists, geologists, mathematicians, chemists – gradually revealed our planet’s hidden architecture.

This glorious unification of varying scientific disciplines, this combining of conclusions, has led us further from the darkness of ignorance. But there is still so much we don’t know.

Is there a Russian-doll-esque inner-inner core? How exactly do the cores interact? Why do they trigger magnetic field reversals? We know so much, and yet so little.

…

As I absorbed these staggering facts, several thoughts emerged.

The first is just a magisterial awe for science – as a process and an institution, and as a collective of extraordinary individuals. Our species’ collective ability to deduce hidden truths through observation, reason, and mathematics is unfathomable. As I read, I kept exclaiming to myself, “How on earth do we know this? And how are people so clever as to have reasoned, then proven it?”. We’ve mapped the structure of our planet without ever seeing it directly.

Attendant to that, however, is a reminder that we really do still know so little. We have only been 1/500th down into our very own planet. As a species, we invented cars (1885), the fax machine, (1843), and screened our first film (1895), all before ever knowing that the earth has a molten core. As we race into space and seek solar-escape, we continue in lacking the answers to seemingly fundamental questions.

In turn, this led also to an unexpected sympathy for our forebears. Of course they took as truth their received religious explanations of the Earth’s provenance. Of course they didn’t arrive at our present suppositions. So incomprehensibly large and deep is the Earth, that no human brain has evolved with an intuitive sense for the world’s actual make-up. I live in the 21st century, with the greatest access to information that any known intelligent species has ever enjoyed. Shame on me for taking such knowledge of science for granted, and for judging earlier folk for not knowing better.

As you go about your day, teeming with low-level anxieties about judgement, lunch plans and life ambitions, don’t just remember that you’re spinning through an infinite vacuum at 1,037 mph on an organic spaceship. Remember too, that you’re balanced on a thin crust floating on a sea of flowing rock, while far below, a star-hot ball of metal spins in the darkness. All your worries, fears, hopes and dreams are, quite literally, surface level.

Leave a comment