Welcome back, dear friends, to what is now the fourth edition of The Bookshelf. I had somehow not saved the original completed draft of this month’s review and lost it. Scraping the outer echelons of belatedness, I almost couldn’t find the impetus to rewrite it, but I have, and I am glad to have done so.

The following is an account of the books I read throughout September, and I’m delighted to say that I loved them all. As ever, I thank you sincerely for stopping by to have a read, and wish you a mightily swell day, or night, and a swell life too.

…

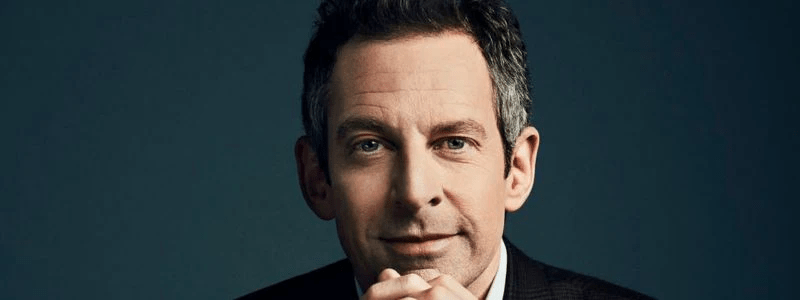

“Waking Up” (2014) Sam Harris

Sam Harris – philosopher, meditator, neuroscientist, secularist, father, husband, atheist, philanthropist – undoubtedly takes the award for ‘Person I have never met, who has exerted the most profound, influential and positive impact on my life’.

After a profound psychedelic experience at the age of 19, after he and his best friend ingested the empathogen MDMA, Harris dropped out of his psychology programme at Stanford to venture to India and the Himalayas. He spent much of the next ten years on silent retreat studying with some of the world’s greatest meditation masters, before ultimately returning to Stanford and completing a PhD in Neuroscience. The following decades have since seen Sam become one of America’s foremost foremost public intellectuals, a best-selling author, and the creator and curator of a meditation app (also titled Waking Up) and a podcast (Making Sense). He is, in my estimation, one of the Western world’s most consistent, clear, rational and fearless thinkers.

Whilst not an accolade of the former order, he also bears credit for facilitating some of the most profound changes I have experienced in the past five years. Teaching me to meditate, encouraging me to pursue direct enquiry into the nature of consciousness, and introducing me to Effective Altruism and the Giving What We Can Pledge. Staging a cast of thinkers and philosophers who now represent some of my favourite minds (Alan Watts, David Whyte, James Low, and Samaneri Jayasāra) and enabling me to spend many hundreds of hours sitting in on the most interesting and perspective-shifting conversations I have ever been privy to.

Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion, charts a path along which a spirituality grounded in science and first-person empirical study, separated from the hangovers of religious dogma and superstition, can proceed unencumbered. Part memoir, part philosophical inquiry and part guidebook, Waking Up features chapters covering consciousness, the self, spirituality without religion, and meditation. This book represents to me a coalesced embodiment of many of Harris’ most defining learnings, thinking, and wisdom. He puts words to experiences that fundamentally transcend language; he presents a rational spirituality not predicated on belief or supernatural claims; and writes with great wit and empathy throughout.

For years I have been intending to write an article titled something like, ‘An Ode to Sam Harris’. Without meaning to, I guess this has become just that. It is without reservation or qualification that I unreservedly recommend him to you, in digital or in print or wherever else you can find him. Sam Harris’ mind, his work, his conversations and his wisdom have touched my life in ways that I cannot overstate, and for that, my gratitude is unbounded.

…

“A Clockwork Orange” (1962) Anthony Burgess

Getting hopped up on ‘milk-plus’ in the Korova Milk Bar, crawling the streets in ultra-stylish ‘droogs’ outfits, and visiting pain on unsuspecting innocents using all manners of torment. For Alex and his droogs, the satisfaction derived from ultra-violence cannot be parallelled. The path that this inevitably leads them down enables the author extant room for exploring questions of autonomy and responsibility, and of state power and individual liberty.

I saw Kubrick’s iconic film adaptation several years ago, and never before have I felt such a profound symbiosis in an author’s and an auteur’s realisation of an idea. I could not shake the feeling that so singular is Burgess’ vision that Kubrick’s realisation could not have been done in any other way. Nor the feeling that Burgess is unboundedly fortunate, to have his vision embodied so lavishly and precisely by Kubrick’s genius.

Nasty, visionary, dark, funny, shocking, thought-provoking and damning, this notorious novel is everything I had imagined it would be. From the jarring, ye-olde, Soviet-twinged Berkovian dialogue, to the visionary imagining of the world in which these cartoonishly construed characters exist, every vein of this book’s being courses with the vitality of originality.

Read the book, then watch the film. Or see the film, then read the book. Either way, you’re in for a delight that ought not to be missed out on.

…

“Storm of Steel” (1920) Ernst Jünger

Ernst Jünger volunteered for the German army in December 1914, at the age of just 19, and fought almost continuously on the frontlines of the Western Front for the following three years. Throughout he incurred several injuries, survived innumerable near misses and astounding statistical improbabilities, and bore witness to some of the most egregious, fruitless, tragic, and brutal desecration of human life the world has ever seen.

By my own admission, I have read only a smattering of books about The Great War, but the feeling resounds nonetheless that this book distinguishes itself as uniquely distinguished for multiple reasons. Foremost amongst these is the evident greatness of the author’s character. Jünger became an officer soon after his twentieth birthday, led many hundreds of loyal and respected men under his command, and finished the war as one of Germany’s most decorated soldiers. Throughout, he is brave, grateful, loyal, unflinching, determined, and human, and a privilege to spend a few hundred pages with.

Not only a man of great character and moral stature, but also a man in possession of an imperiously cool intellect. Jünger provides a considered, illuminating, stoical, and philosophical autobiographical account, making tangible what is so distantly chaotic. With deft strokes of seemingly sparse and economical language, he communicates expertly the atmosphere, imagery, and cruelty of trench warfare, as well as the extraordinary spirit, courage, duty, and selflessness exhibited by these painfully young men.

Most astounding, however, is the sheer improbability of his surviving to write this account. During his time on the front lines, he suffered several injuries, survived innumerable near misses, and conquered astounding statistical improbabilities. The book is replete with comrades killed beside him, shrapnel embedding itself in miraculously fortuitous places, and bullets and shells whizzing right beside his head. Not only does this relay the scale of death and destruction to the reader, but it inadvertently allows also Jünger to create a running account of the changes in warfare. By surviving so long he sees the introduction of more refined shells, grenades and rifles, followed by the introduction of flamethrowers, gas attacks and weaponised planes.

A stark reminder of how fortunate I am to be a 23-year-old man not yet exposed to such brutality and horror. This account provides a testament to the glory of peace.

…

“Animal, Vegetable, Miracle” (2007) Barbara Kingsolver

In 2004, the author Barbara Kingsolver, her husband and their two teenage daughters left the barren and inhospitable desert cities of Arizona, to begin life anew on a small-holding farm in rural southern Appalachia. Animal, Vegetable, Miracle chronicles the following year, in which the family tries to live only on the produce they grow themselves, or that they source from other farms within their county.

70% of Americans are obese. Heart disease is the nation’s leading cause of death. Their life expectancy is five years below that of the U.K.’s, and almost ten years below that of Japan. And its modern food production system ought to take the brunt of the blame. Millions of tonnes of toxic pesticides poisoning the land, supply chains which bring fresh strawberries and mangoes from the other side of the world and pollute extraordinarily, and unprecedented quantities of ultra-processed food containing fats, sugars and salts in our diets that we should never be consuming in the first place.

Kingsolver asks how we have gotten to such a place and answers emphatically. Greed, lies, laziness, corruption, advertising, city-ification, and alienation from the production of our food. More importantly, however, she asks how we can solve these problems. By paying greater attention to what we eat, by sourcing our food locally, by supporting local agricultural economies, and by taking back our stake in the food that we consume. She is not bible-bashing nor prophesying. Instead, she is loving and rejoicing, consistently spellbound by the majesty and miraculous nature of nature.

This is a book so warm, that you can guarantee your cockles will be toasty for many weeks to come. Kingsolver writes with such adoration and admiration for food and the processes by which they come to be, that one cannot be swept up along with her. It is a book soaked in colour, such as it feels the palette of her Virginian farm seeps through its pages. The first shoots of asparagus, the sweetness of real tomatoes, the delights of foraging for mushrooms. With her sleeves ever rolled up and her elfin smirk unerringly challenging, she holds up a clarifying mirror to the insanity which is our food production processes and supply chains.

Leave a comment